Coubertin is One of History’s Greatest Forgotten Heroes

FrancsJeux.com

10/4/2013

Interview with Alain Mercier

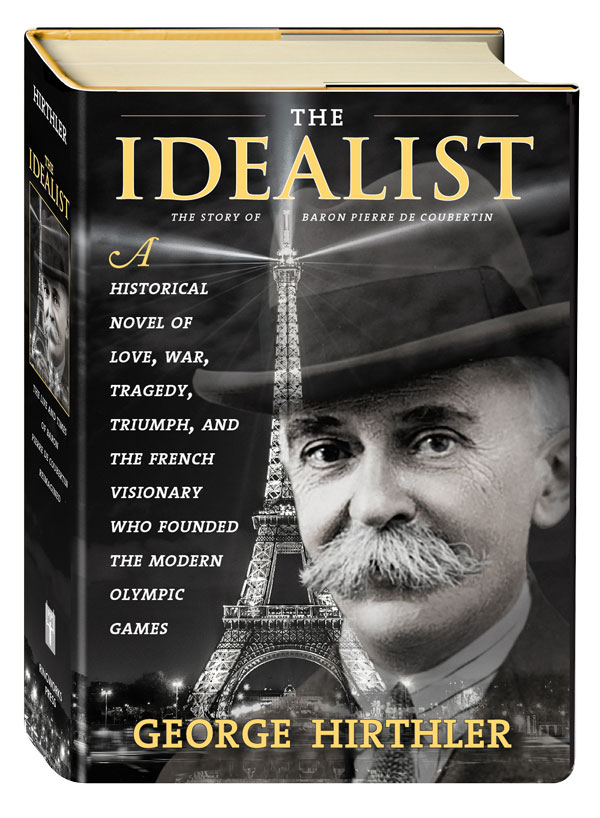

In 2013, the Olympic Movement celebrated the 150th anniversary of the birth of Pierre de Coubertin. The French Baron who invented the modern Games continues to inspire new generations, but his legacy is little known around the world, especially in the United States. As a preview to the upcoming release of the biography entitled The Idealist, the author, American George Hirthler, an expert consultant in the Olympic Movement, answered some questions for FrancsJeux.

1) Why did you decide to write a book on Coubertin?

Let me give you three reasons to begin with: 1) If you examine the impact of his life, work and ideas on our world today, it is nearly impossible to conclude that he is not one of the most influential and important people born in the 19th Century. 150 years after his birth, his legacy is only growing stronger, reaching deeper and deeper into every nation on our earth, putting sport at the service of humanity everywhere, inspiring millions of children to play every day. 2) Today, we live in a world divided by war, animosities, terrorism, religious and ethnic conflicts. We lack the international will to form a lasting peace between nations; we cannot find the common ground we need to unite us. But here is a man who envisioned the possibilities of global friendship and peace through sport and created a worldwide festival that does what no other modern institution has been able to do—unite us in a great recurring celebration of humanity that reminds everyone—4.5 billion people watched some part of the London Olympics—that we can find common ground, that we can rediscover in each rising generation the noble values we all share, and that there is hope for a better world. 3) I think his story is fascinating on multiple levels. He was born on January 1, 1863, the very day that Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation—and he turned sport into one of history’s greatest forces for social liberation. Although he was born into the aristocracy, he embraced the egalitarianism of the Third Republic and spent his life finding ways to educate, liberate and create opportunities for everyone. He straddled the two centuries—living 37 years in the 19th century and 37 years in the 20th century—and he harnessed the power of international transformation that was reshaping our world to change the world of sport. I’m amazed that France has not embraced him as one of its greatest citizens historically—and even now—since his work clearly embodied the full promise of modernity that made Paris the cultural capital of the world across the centuries.

2) Is your book a typical biography?

No, The Idealist is a work of historical fiction. While most of the historic dates, important events and personalities of his life and times are depicted, fictional characters of my invention move on and off stage, interacting with the real figures in ways that allow me to reimagine the settings and circumstances of Coubertin’s milieu. In setting out to write this book, I wanted to give readers a new level of imaginative access to Coubertin’s life, introducing him at a level of intimacy known only to best friends and family. My goal is to make him as well known as his Olympic legacy. I’m hoping this novel will help popularize his story because I believe that Baron Pierre de Coubertin is one of history’s greatest forgotten heroes. I am constantly amazed by the fact that his Olympic legacy is known to billions, but his name has been lost to all but a small circle of Olympic athletes, workers, devotes and academics. One more point—Coubertin was a visionary, but like so many far-sighted men, he also had his blind spots, particularly when it came to women in sport. Fiction, unlike fact, gives me the ability to deal with these blind spots directly, challenging him to face his own shortcomings.

3) What does the name Pierre de Coubertin mean in the US?

Other than in a few academic circles, his name means very little. And that’s not surprising. It’s that way in almost every nation. Perhaps in France and England, and certainly in Switzerland, his name might have some level of recognition, but not even a fraction of the awareness it deserves. I think it is a shame that every living Olympian—and there must be 70,000 or 100,000 Olympians alive today—aren’t schooled in the lessons of his life and the values of the Olympic Ideal. They should all be ambassadors of his name.

4) In your opinion, is Coubertin’s heritage still strong?

Not only is it strong, it is growing stronger on a worldwide basis today. The Olympic Movement is still breaking down barriers and expanding as a global sports industry. And the TV audience for the Olympic Games is still growing. If you look at it in historic terms, the first century of the Olympic Movement was all about building the global infrastructure of sport, creating the international standards for competition, spreading the Movement country by country, developing national Olympic teams everywhere. Over the last 50 years, broadcast television and sponsorship have turned the Movement into an industry, and yet, we’re still only 119 years from the founding of the modern Games by Coubertin and his colleagues at the Sorbonne on June 23rd, 1894. In Ancient Greece, we know that the Games lasted for 12 centuries. Imagine what the future might hold for the modern Olympic Movement if it’s still going in the year 3,094. I believe that if the Olympic Movement finds a way to put Coubertin’s vision and his ideals at the center of its vision for the future—pushing harder to return to an educational focus on the values of sport—the reach, influence and prestige will only expand and grow. The philosophy of Olympism that Coubertin created is the most valuable asset the Olympic Movement possesses. Recognition of that fact, and what do to with it, is the great puzzle the IOC needs to solve to guide the Olympic Movement to ever greater heights of excellence.

5) What would Pierre de Coubertin think about the IOC and the Olympic Movement today?

He would be proud of the extraordinary scope, scale and reach of the Olympic Movement and the brilliant quality of the global broadcasts that carry his Games to every corner of the world. He would be enthralled by the intense drama and record setting excellence in the competitive cauldron of the Games. But he would be saddened by the loss or the ineffective nature of the educational emphasis in the Movement—the lack of teaching of the Olympic Ideals. He would applaud the fight against doping that the International Olympic Committee has so aggressively led. But he would find, I believe, the ethical issues that have haunted the IOC and many of the IFs a reprehensible betrayal of the universal drive for excellence the Games and the Movement are meant to embody and model. Nevertheless, on the whole he would be filled with affirmation that his vision had come to life, exceeded his expectations in many ways, and still held promise for even greater achievements in the centuries to come.